Despite the retail industry’s current tumultuous atmosphere—or perhaps because of it—many retailers are focused today on expanding their operations and scaling their businesses. As we touched on in a recent post on the RevCascade Blog, the changing tides of the retail industry mean that companies need to be aggressive and proactive in 2017, not defensive and stagnant.

Having said that, not all growth efforts are created equal. In today’s uncertain retail environment, there is no one-size-fits-all formula for retailers, and the costs to test and fail are higher than ever. Out of the most common ways for retailers to expand, then, which is the least risky and most likely to have the best ROI? Let’s consider the options.

Expanding brick-and-mortar (opening new stores):

Opening a new brick-and-mortar location can be a worthwhile endeavor, depending on what your business is and what the purpose of the new store is. There are obviously dozens and dozens of variables, but if we consider the start-up costs alone, it’s apparent that opening a new storefront requires significant overhead and is inherently risky from an ROI perspective.

Here is just a sample of those start-up costs, with input from personal finance website The Balance:

- Labor costs, including store employee wages, insurance, benefits, and training

- Building/real estate costs, including rent, deposit, renovations, insurance, fees and permits through the city, state, and federal governments

- Storefront/equipment costs, including utilities, office supplies, POS software, accounting software, store fixtures, furniture, computers, cash registers, security cameras, etc.

- Inventory costs, including initial inventory to sell in the store on opening day, as well as regular replenishment of stock and warehousing costs

- Logistics costs, including warehousing and delivery personnel and equipment if delivery is offered

Clearly, getting a brick-and-mortar store up and running and profitable is a multi-faceted process with significant upfront costs. There are multiple one-time fees, like the storefront/equipment purchases, but there are also substantial long-term, recurring costs to consider, like paying your employees and holding and distributing inventory.

While opening new storefronts has always been somewhat risky, the state of retail today makes it even moreso. 8,600 storefronts are projected to close this year, and closures have already risen 200% YOY in 2017. The necessary long-term investments in brick-and-mortar are riskier than ever today.

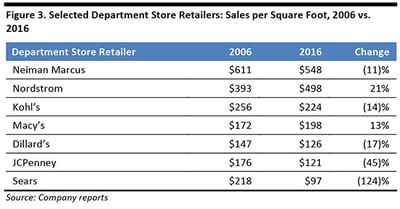

"Simply put, it all comes down to productivity," said CoStar Portfolio Strategy’s Director of Research Suzanne Mulvee in a recent report by the firm. "Retailers on average are generating fewer sales per square foot than they did during the decade leading up to the recession."

This is especially true for department stores, as we can see in the table below. According to the research firm Fung Global Retail & Technology, five out of the seven major department store chains they analyzed for a recent report experienced declines in sales per square foot over the past 10 years. Sears’ stores saw the biggest drop in productivity, 124% over the period.

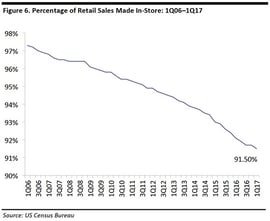

While in some cases the risks of taking on brick-and-mortar square footage may pay off, in general, opening physical locations for selling purposes is quickly becoming an antiquated way to grow retail businesses. Most stores are seeing plummeting store productivity, and as the graphs below show, brick-and-mortar as a whole is rapidly losing its influence over retail. While in-store sales still account for about 90% of U.S. retail sales, that number is shrinking every year. Ecommerce sales, meanwhile, are seeing exponential growth.

.png?width=466&name=fredgraph%20(1).png)

As an alternative to opening stores and holding/selling inventory, many of today’s most innovative companies are experimenting with lower-cost physical presences solely for customer experience and marketing purposes (if they’re opening physical spaces at all.) That’s due to the crucial understanding that physical stores are not necessary for the sale and distribution of goods. Amazon, Alibaba, and eBay have been shining examples of that fact for years now—Alibaba of course became the world's largest retailer (ecommerce or brick-and-mortar) last year.

So for those considering expansion through brick-and-mortar: yes, there is still absolutely a place for physical retail, but the overhead and upfront cost of opening new stores is risky in today’s economy and, in most cases, is simply not necessary if your goal is to sell more merchandise.

Expanding ecommerce store:

As is the case with opening physical stores, there are many ways to expand your online wholesale operations and many variables to consider when trying to do so. Your upfront costs are obviously going to differ depending on what stage your business is in and what ecommerce infrastructure you already have in place.

Regardless of those considerations though, the biggest overhead cost when expanding online wholesale operations is almost always inventory. Whether you’re an already-successful retailer with $100 million in annual revenue or a young startup, if your ecommerce site runs on a wholesale model (buying in bulk from suppliers and then reselling to the end consumer), inventory will carry inherent risk.

There’s a lot to like about the wholesale model. For one thing, it’s familiar—most multi-vendor retailers have wholesale experience of some sort. For another, it lets retailers feel like they’re more in control of their merchandise because they have physical products on hand. However, holding inventory is risky and is also extremely limiting from a product assortment standpoint.

There are many ways in which retailers can be harmed by holding inventory. The crux of the problem, however, is that retailers essentially spend millions of dollars up front to build their inventory, only to then face the very real danger that they might not be able to sell that merchandise or have to sell it at a loss. One other consideration is that physical stock can be damaged, lost, or stolen, resulting in major hits to their bottom lines. In 2016, in fact, the total U.S. retail economy lost an astounding $48.9 billion worth of products due to inventory shrink alone.

But that $48.9 billion figure doesn’t even take into account all the money that retailers lose when their inventory simply lacks consumer demand and is unsellable. It’s a totally unavoidable problem for retailers who operate via wholesale—when they buy from their suppliers up front, it’s impossible for retailers to be one hundred percent certain which items will appeal to consumers and how much of each SKU to buy. Inevitably, some items fail to sell, and they then become “dead inventory.”

“Dead inventory” is the omnipresent, silent killer of all wholesale retailers, as a recent article in The Business of Fashion explained. Due simply to the nature of the model, retailers who sell via wholesale (whether they’re brick-and-mortar, online, or both) face the inherent risk of unsold stock and devastating financial losses. As an industry standard, only about 60 percent of a retailer’s initial inventory will be sold at full price, according to BoF. Of the remaining 40 percent, the retailer will hopefully be able to liquidate some portion, but the remaining unsold items are lost to “dead inventory,” a category that costs the U.S. retail industry an additional $50 billion per year.

While wholesale is risky for retailers, the greatest benefit of the model is that retailers’ margins are generally better than they are in the alternative model, dropshipping. Due to the fact that they’re incurring the inventory risk and bringing the supplier huge revenue in one fell swoop, retailers are usually permitted to buy product at very low wholesale prices compared to the price they’re actually going to sell it for on their shelves and website. Though it varies significantly by industry, by company, and even by product, it’s not uncommon for wholesale retailers to realize margins of 30-40 percent.

Expanding via online wholesale requires less overhead than opening a new brick-and-mortar store, is on the right side of the ecommerce boom, and offers favorable margins for retailers. However, those benefits might be outweighed by how risky the model is due to its inventory commitments, and by how limiting it is from a merchandising perspective, something that we’ll go into further below.

Expanding dropship operations:

By its very nature, dropshipping, the fulfillment method wherein a consumer places an order with the retailer but the manufacturer/brand is the one to ship the order directly to the consumer, is the least risky method of expanding sales for retailers. For one thing, running an online dropship program (also known as a “marketplace”) can be done with zero upfront physical costs. Rather than opening a store and facing all the costs mentioned above, retailers who choose to dropship can sell thousands of items online without expending any physical capital.

Of course, that freedom from labor costs, real estate costs, storefront costs, etc. is also a huge benefit of running an online wholesale shop. So why is dropshipping less risky than wholesale? It comes back to inventory. As was noted above, selling wholesale requires taking on inventory, which inevitably threatens your profit margins. Dropshipping, on the other hand, requires no such inventory risk. A dropshipping retailer does not keep any physical products in its store – it simply transmits order information from its website to the brand, which ships it onto the customer. This of course means that the retailer faces almost zero overhead, but it also means that the retailer is not limited at all with respect to the products it can sell.

In addition to inventory shrink, devaluation of supply, and dead inventory, wholesale is a severely limiting option when it comes to product assortment and profit maximization. A wholesale retailer can only sell the products and the inventory that it has in stock. That means that if the retailer only has 1,000 square feet of storage space, the only things that can be sold are the physical items in that space.

Retailers who dropship, meanwhile, have an unlimited supply and mix of products to offer their customers, making merchandising a breeze and fully optimizing their profit-generating potential. They can form partnerships with countless brands who dropship, curating the perfect mix of products for their customers.

RevCascade client Maisonette is an excellent example of this. The online marketplace for kids’ merchandise has no brick-and-mortar presence whatsoever, housing the whole company in Brooklyn, New York, and it runs a 100% dropship business that takes on zero inventory. That means that its website can offer a dress from a boutique in Paris right alongside a rug from a designer in Los Angeles, all without taking on any physical inventory and its associated risk.

What’s crucial to remember about dropshipping, though, is that you absolutely do not have to be a 100% dropship marketplace company like Maisonette to successfully engage in the practice. In fact, those “traditional” retailers who wish to expand their online sales to compete in today’s tough retail environment are the perfect candidates for launching a dropship program. Dozens of such “traditional” companies, RevCascade client Crate & Barrel included, have launched their own dropship programs in recent years as a way to add a new, lucrative, low-risk revenue stream to their existing business models. Their efforts have helped them stay competitive while others have fallen victim to decreasing market share at the hands of ecommerce giants like Amazon, eBay, Wayfair, and Overstock.

Dropshipping is not entirely risk-free though. If brick-and-mortar expansion’s primary risk is the upfront costs of physical capital, and online wholesale expansion’s primary risk is inventory, dropshipping’s primary risk is logistics and technology. There are many many moving parts behind a successful dropship program, and communication between a retailer and its dozens of suppliers can be a data nightmare. Retailers need to make use of the best marketplace technologies, otherwise they’ll risk lost orders, misrepresented inventory, and unhappy customers.

Thankfully, however, there are effective dropship solutions out there that can streamline entire dropship programs/marketplaces and allow retailers to sell thousands of products through their extended aisles. As was mentioned earlier, dropshipping does generally have margins that are more favorable for brands/suppliers than for retailers, given that the supplier still carries the burden of inventory risk. However, the risk for retailers is almost non-existent, and they can immediately expand and see positive ROI, something that’s of the utmost importance in today’s retail environment.

Conclusion:

In today’s economy, every retailer is looking for high-impact, scalable growth initiatives with as little risk as possible. When evaluating each of the three methods of expansion above, it is clear that each method has its pros and cons. But overall, though online wholesale selling may have better margins on a SKU-by-SKU level, launching a dropship program or marketplace—or scaling the operations of an existing one—is the most ideal, turnkey, flexible, and risk-free way for retailers to grow their businesses.